Looking at Facebook Telescope Addict page you notice a trend in amateur astronomy. There are hundreds of terrific pictures of planets, galaxies and nebula, but very few images or comments on stars! Up until the 1950’s much of astronomical efforts had to do with stars, with a few notable exceptions. How hot they are, their precise positions, distance, color and composition led the thousands of scientific papers that poured from universities all over the country. Recently the Gaia data releases have brought some focus back to stars but it is just a small blip on some professional astronomers radar.

For those of us that started early in life to look through telescopes, we spent hours looking at the stars and never could get enough. Double stars, colored stars and groups of stars were all terrific targets for small kids with small scopes. The joy of just looking at the stars took us far. In our current day, quality cameras and equipment have moved us to imaging really cool nebular stuff and away from stars. These nebular objects were hard to photograph back in the days of film even with large telescopes. (See my comparison of the 200″ Palomar scope and an 8″ reflector here… http://templeresearchobservatory.com/palomar-vs-tro//). Virtually every professional observatory during that time had major studies of the stars going on. Where has the interest in the stars gone? Why don’t more amateurs and professionals alike spend time on these objects?

The common perception is that we know just about everything that we need to know about stars. Wow is that a misconception! In the fall of 2010 while imaging M 57 or the “Ring Nebula” with a 6″ refractor, I found myself wondering if the Blue White Dwarf star that forms the heart of the nebula was variable. As a freshman in college I remember looking through the 24″ refractor at Lowell Observatory after the public session. This was back when I was young, good looking, a college running back at a DIAA college and the telescope operator was a pretty coed! After looking at a few pretty objects the operator turned to M 57 in Lyra. Upon putting my eye to the scope a small purple star floating in a green ring of gas popped out and hit me in the face! It was beautiful! This is probably the time when Stars became Stars to me!

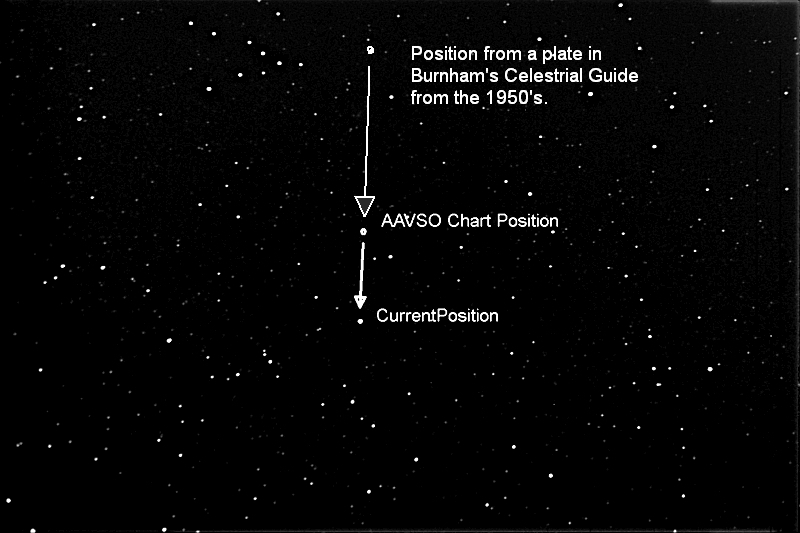

Though the behavior of white dwarfs was well known in some circles, few professionals or amateurs that I talked with had a clue whether it was variable. Burnham’s guide said it was variable by 1 magnitude and several catalogs listed it as variable but no one really knew. After contacting every professional astronomer I knew (and some I didn’t know) the common answer was “I don’t think so but why does it matter?” Arne Hendon of the AAVSO, Arlo Landolt of Louisiana State University and Rik Hill of the Catalina Sky Survey were the only ones who knew about the possibility of variability and encouraged me to study it.

Turns out it is variable! In fact most white dwarfs are variable! Howard Bond and Al Grauer in the 1970’s and 1980’s found numerous dwarfs that exhibited variability. The average variability is around 2% so it is hard to detect but definitely in range of many of today’s amateur telescopes. In a short run with the AAVSONET Wright 28 Telescope (11″ Celestron SC with a SBIG ST-7E camera) the variability followed the predicted amount of 2%. Using this data and some Kepler spacecraft observations for comparison in a poster at the Kepler Science Conference in 2011, it caused some surprise from many established scientists (though they also indicated that it was not all that important!). The majority of those that took time to look at the poster had no clue that white dwarfs were variable. The common question was “What mechanism would cause that?”

Some of the best guesses are sunspots, long term flares, gravity waves or shell fusion. Bond and Grauer found that some dwarfs actually had similar light curves to pulsating variables but on minute scales, not hours or days like larger stars. Since white dwarfs are made out of degenerate matter where a teaspoon of dwarf matter weighs a ton makes this unlikely. Around many dwarfs there are thin, 20 kilometers or less, shells of hydrogen or helium gas. So if the star is pulsating it is only pulsating in that thin gas envelope.

The most interesting possibility is gravity waves and the most likely. If you saw the movie “Interstellar” you will remember the giant wave that almost destroyed the ship and people…that’s a gravity wave. Imagine a wave of 100,000 K gas, 20 kilometers or more high, racing completely around the white dwarf in minutes! If that is not a cool picture I don’t know what is!

Two really interesting books about “boring” stars are “The Hundred Greatest Stars” by James B. Kaler and “The Brightest Stars: Discovering the Universe Through the Sky’s most Brilliant Stars” by Fred Schaaf. Both of these books are on the most interesting bright stars in the sky. A case in point is the strange star of Beta Lyra also called Sheliak. This is an easily seen naked eye star in Lyra. It is often used to help find M 57 but deserves a good look from time to time on your way to the Ring. The main star is a Blue Class B giant star with a Class B dwarf star 30 solar diameters away from it. They are so close together that gas is being sucked into the smaller dwarf star. Some of the mass flowing from the larger star to the smaller is lost to space and creating a tail behind the pair! Both of these books are filled with really interesting facts and stories about these brighter stars. Definitely worth a look in the book and in the sky as well!

So are the stars no longer Stars? Don’t think so! In fact with the increasing sophistication of equipment, smaller and smaller telescopes can turn out professional top quality data. As professional astronomy gear gets more and more expensive, it is falling to amateurs to continue much of the work that the observatories and universities used to do. Groups like the AAVSO and BAA are still viable and provide high quality Visual/Imaging data to researchers both professional and amateur. If you have an interest in actually doing science I would encourage you to go to https://aavso.org/observing-manuals and read the visual or CCD photometry manuals. These are free and point you toward where you can use all that expensive equipment, binoculars or even naked eye, to actually do science!

Next clear night take some time to look at and appreciate these bright jewels of the night sky. If you are an imager take some star pictures of the stars as well! Make the Stars, stars again!